John Berry had been born in the Barrabool Hills just outside Geelong on Oct 7th 1854. 1 His father, a farmer also named John, was a native of Co.Tyrone, Ireland, having been born near Strabane around 1821 who arrived at Port Phillip as a bounty immigrant aboard the "Catherine Jamieson" accompanied by his older brother James. The "Catherine Jamieson" had sailed from Leith (near Edinburgh) Scotland on 29th May 1841 and arrived at Port Phillip on Oct 22nd of that year. The "native place" of the brothers was recorded as Co Tyrone and both could read and write. 2

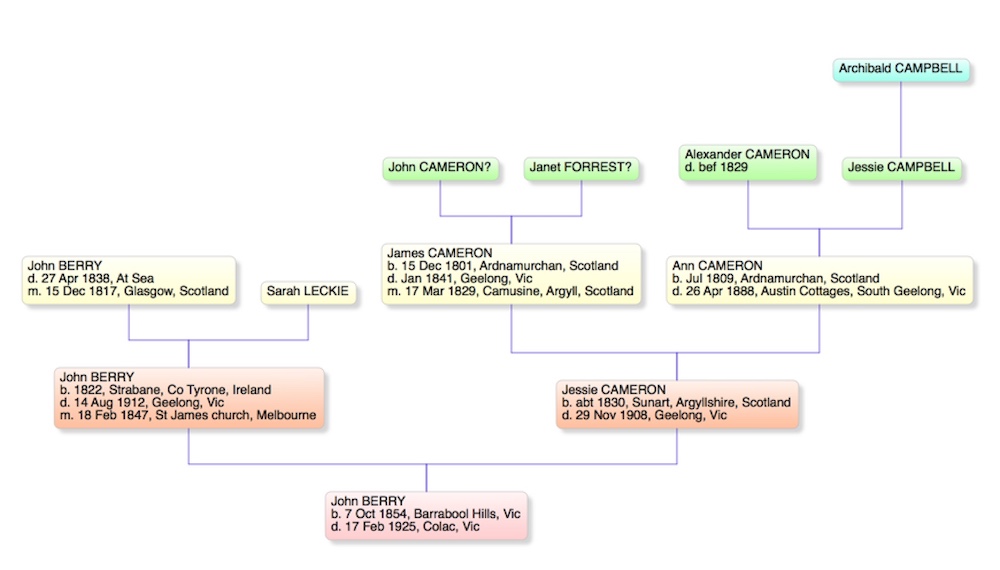

Ancestry of John Berry

Although born in Ireland, one of John's parents seems to have been a native of Scotland. At least Sarah Leckie was living in Glasgow when she married a soldier of the 40th Regiment of Foot named John Barry, on 15th Dec 1817. 3 It is now known that John Barry joined the 2nd battalion of the 40th Regiment at the Phoenix Park barracks in Dublin, on 5th April 1813. No date of birth was entered on the enlistment form which was required if he was under 18 years of age. Obviously then it would seem that John was Irish, as were many, even most, soldiers in the British army at this time, but nothing more is known of his origins or his family.

Through the quarterly muster rolls of the 40th Regiment John's subsequent military career is well documented. He was stationed initially with the second battalion at Athlone and Mallow in Ireland, then Plymouth in England, before being transferred to the first battalion of the same regiment which arrived in Brussels in 1815, just in time to play a significant part in the battle of Waterloo on18th June. "At Waterloo the 40th were at first in reserve but later were moved into the centre of the allied line, near the farm of La Haye Sainte. There, like the 30th, they withstood repeated attacks by cavalry and infantry and were pounded by cannon, but they stood firm. Towards evening they drove back Napoleon's final attack by massed infantry. Shortly afterwards the Duke of Wellington personally ordered the Regiment to advance. The 40th charged, swept away the French infantry to their front and took part in the recapture of La Haye Sainte. One quarter of the Regiment fell that day. For their steadfastness and discipline at Waterloo the 30th and 40th were permitted to encircle their badge with a Laurel Wreath. The battle is commemorated annually by the Regiment." 4

Following Waterloo, John was stationed near Cambrai in France performing garrison duty with his regiment before being posted to Glasgow in late 1816 or early 1817. Presumably it was here that he first met Sarah whom he married in Dec of that year. The 40th stayed in Glasgow until 1819, then was based in turn at Sunderland and Rochdale in England during the following year. At about this time the couple's first son, James, was born at Greenock, near Glasgow. Their second son John however was born near Strabane in Ireland. This is something of a puzzle as although John was stationed in Ireland from late 1820 none of the locations in which he found himself:- Ennis, Co Clare; Templemore, Co Tipperary; Newcastle, Co Down; Buttevant, Co Cork; Athlone, Co Westmeath or Dublin were anywhere near Strabane or Co Tyrone. I will return to this point later.

In 1823 John formed part of a detachment of the 40th Regiment that embarked for Australia aboard the "Medina" accompanying 177 Irish convicts on their voyage into exile. Possibly for John this was to amount to a more severe punishment than that given to those who had been convicted of crimes, as it seems probable that he never saw his family or native land again. Upon arrival in Australia he spent time at Parramatta, Bathurst and Moreton Bay (Brisbane) before embarking for Van Dieman's Land in late 1825. He then spent almost a year at the penal settlement of Maria Island with shorter periods at Port Dalrymple, Norfolk Plains (Longford) and the Clyde (Bothwell). 5

Convict ruins, Maria Island

The duties performed

by the British Army Regiments in Australia were varied and sometimes

onerous as the following passage suggests.

Apart from those connected with the system of convict

transportation, both afloat and ashore, they established and maintained

the Mounted Police in New South Wales between 1825 and 1850.

The troops constructed fortifications; attended fires and executions; assisted the police in keeping the peace between rioting

sailors, rival election parties and squabbling sectarians.

They provided guards for wrecks, goldfields, colonial treasuries,

quarantine stations, government houses and the opening and closing of

legislatures and mounted escorts for gold in transit.

They manned coastal defences and fired ceremonial artillery

salutes. They also operated intermittently against aboriginal

resistance in most of the colonies. 6

John Barry's regiment was then posted to India in late 1828, although John did not join them immediately, only reaching Bombay on 10th June 1829. He then served in India for almost nine years being based successively at Bombay, Poona, Colaba and Deesa. His service however was interrupted with several periods of hospitalisation. Probably he was over forty years of age by this time and the climate and harsh nature of military life had taken a toll on his health. So much so that on 8th Jan 1838 he boarded the "Boyne" with a group of soldiers classified as "invalids and men for a change of climate" which set sail for England. Unfortunately he never reached "home". He died on board ship on April 27th and was buried at sea.7

Some insight into just how difficult the life of the common soldier was at this time can be gleaned from the following:-"As late as the 1870's a soldier was issued with his uniform, a mattress, a pillow, blankets and a pair of sheets. The blankets were seldom washed, fresh sheets issued once a month and new straw for the mattresses once a quarter. The soldier's working day began at 6.30am and ended well after sunset. Sunday was supposed to be a rest day but it included a full-dress church parade followed by an inspection of stables and quarters by the commanding officer. The extra work involved ensured that Sunday was anything but a day of rest ...

Peacetime rations were scant. Up to the Crimean War there were only two meals a day - at 7.30am and 12.30pm. Until the 1870's the only food issued was 12 ounces of meat (usually of poor quality), a pound of bread and a pound of potatoes for which sixpence a day was deducted from the soldier's pay. Any additional foodstuff had to be paid for out of what was left. Even at the end of the century the last meal of the day was tea at 4pm. This consisted of tea, bread and butter.." 8