Woolpack Inn at Warehorne. Dating from the 16th century the inn and the church opposite would have been familiar sites to Thomas Benstead

CHAPTER SEVEN Kent:- A Convict Ancestor

Thomas Benstead was the son of another Thomas Benstead who had married Hannah Brooker on 6th February 1815 at Tenterden in Kent, England. All of the couple's seven children were christened at nearby Warehorne, and Thomas' occupation was recorded as being "agricultural labourer", an occupation that in turn was to be taken up by his son Thomas. Thomas Jr was the fifth child born to Thomas and Hannah, and was christened on 12th Nov 1826. Warehorne is a small village in Kent on the edge of Romney Marsh - a flat, low-lying area in south-east England which became famous in the 19th century for its breed of sheep whose major characteristic was an ability to feed in wet situations, and which was considered to be more resistant to foot rot and internal parasites than any other breed. Improved methods of pasture management and husbandry meant the marsh could sustain a stock density greater than anywhere else in the world. From the 17th through to the 19th century the area around Romney Marsh was notorious for smuggling - its sparse population and proximity to France across the English Channel making it ideally suited for this activity. The parish Church of St Matthew in Warehorne reportedly still contains a tunnel used by smugglers linking the church to the nearby Woolpack Inn. The family of Thomas had a long had a long association with the area. His father Thomas was born in Warehorne in 1786 and his grandfather, who was also named Thomas, was born in nearby Woodchurch and married Abigail Russell at Warehorne on Oct 19th 1771. Abigail was born in Bethersden, the eldest of four daughters of Thomas Russell and Sarah Horton. Other paternal ancestors of Thomas (b 1826) included Richard Kemp born in Great Chart in 1672 and married to Ann Webb in Shadoxhurst in 1698, whilst his mother Abigail's ancestors included her father Richard Brooker from Tenterden, whose wife Sarah (or Hannah) was from nearby Rolvenden where here family had lived for many generations. Warehorne, Bethersden, Great Chart, Shadoxhurst Tenterden, Woodchurch and Rolvenden are all in Kent and within about a 15 km radius of Warehorne 1

Woolpack Inn at Warehorne. Dating from the 16th century the inn and the church opposite would have been familiar sites to Thomas Benstead

Warehorne church and graveyard

It would seem that farm labouring was not the only activity that the younger Thomas Benstead engaged in. On 10th March 1845 he was convicted of breaking into a house and stealing a sum of money, a pair of shoes and a bag from his former employer, one Stephen Norley (or Nutley) at Great Chart. He was sentenced to ten years transportation to Tasmania.

One can only speculate on the circumstances that led Thomas to commit this crime (presuming he was not wrongly convicted). Perhaps he was desperate to support his wife with a young child on the way, perhaps he felt he was owed something by his former employer, or perhaps it was just an act of bravado of a foolish youth - he was only nineteen after all. His trial was widely reported. An account from the 'South Eastern Gazette' reads as follows:-

HOUSEBREAKING.

Thomas Bensted, 19, was indicted for stealing from a dwelling-house, 40s., pair of half-boots, value 10s., and a bag, the money and property Stephen Norley, at Great Chart. Sir Walter Riddell prosecuted and Mr. Russell defended the prisoner.

Eliza Hughes deposed that she was housekeeper to the prosecutor, who went to Ashford market on the 21st January. Hearing a noise about twelve o clock, she sent a servant girl to the garret, who was unable to get in. She went up stairs some time after, and saw a hole near the lock of the door in the men's room, large enough to admit a hand. Prisoner had lived with her master some time before. When her master came home at five o' clock, she went with him up stairs, and found the garret door open; on looking out of the window saw the prisoner run away from the house; and after he had got a short distance he dropped something. When he turned round to pick it up, she saw his face. There was hole in the ceiling of the men's room, which was over that in which she slept, large enough to admit a man.

Cross-examined. It was very moonlight. Thought the prisoner had on a black hat. Did not see him in the house. When he turned round she saw his face, but knew him before. Did say that she knew it was the prisoner before she saw him.

The prosecutor deposed that the prisoner left his service on the 10th October. When witness came home from market he went up the stairs, with the last witness, leading into the men's room. His housekeeper looked out of the window, and mentioned to him the name of person. Saw a rope hanging out of the window. In the corner of the room there was an old bed-tick, on which some person appeared to have been sitting. On going to his own bed-room he found his drawer open, and the above money missing, which had been safe in the morning. Went into the men's room, in which was hole near the door-post. The key belonging to the garret hung in the kitchen, but was missing that day.

He got assistance, and traced the footsteps of a man from the window about fifty yards, leading to the railway station, which is about three miles distant. On the next day witness and neighbour traced the footsteps a mile and half further towards the station. Did not see the footmarks compared with with any shoes.

Samuel Bright deposed that on the 22nd January he went with the prosecutor, and traced the footmarks from the house to the railway station. He then went to Tunbridge, where he apprehended the prisoner. Cross-examined. There were the marks of only one person. Evenden, constable of Bethersden, took the prisoner's shoes, which had been in his possession ever since.

Charles Terry deposed that he was in the service of the prosecutor. The half-boots produced belonged to him, and were taken from his bed-room adjoining that in which the maidservants slept. He also lost at the same time two half crowns. Mr. Russell addressed the jury for the prisoner. Transported ten years.

Whatever the circumstances, ten years seems a severe sentence. Nevertheless, although it is difficult to get an exact comparison, depending on the criteria used (purchasing power of goods and services, wage value etc) the amount stolen could equate to anything between 500 and 3,800 Australian dollars (2017 values). Another comparison can be made with the amount of 55 pounds per year paid to James Bond on his arrival at Portland a little over 10 years later (see Ch 2) which means the amount stolen by Thomas was more than two weeks wages - a not insignificant amount! Had Thomas committed the offence half a century earlier, he may well have been executed, but from 1808 onwards there was progressive reform, which by 1841 had reserved capital punishment for more major crimes. The death penalty for theft was removed in 1832 - fortunately for the descendants of Thomas!

Thomas was transported aboard the "Marion" which sailed from Woolwich on the 14th June and arrived in Hobart on 16th Sep 1845. A surviving document located in the UK national archives mentions that on the voyage to Van Dieman's Land Thomas was placed on the sick list from June 20th to June 28th suffering from rubeola (measles. He subsequently worked in a labour gang at Darlington on Maria Island (co-incidentally where another ancestor of mine John Barry or Berry had served as a prison guard almost 20 years previously.) There is no evidence to suggest Thomas was an habitual criminal. The surgeon's report on the "Marion" states that he was well behaved and he seems to have been a model prisoner, to the point where he was granted a conditional pardon after serving seven and a half years. His later life also seems to have been above reproach.

The convict records reveal that he was married, with his wife's name given as Caroline and the records also give the names of his parents, Thomas and Hannah, and siblings James, Jane, Anne, Sarah and Charlotte. The marriage of Thomas Benstead to Caroline Day took place at Great Chart, a village on the outskirts of Ashford about 8 miles from Warehorne, on 2nd Sep 1844. A child named Mary Ann was born on 1st Feb the following year but lived only a few days. A little over a month later Thomas was convicted and sentenced. This event must have been traumatic for Thomas and his family, and especially for his young wife, as the couple would have realistically had to resign themselves to the likelihood that they would never see one another again. 2

On completion of his sentence Thomas seems to have decided to put his past behind him and move to Geelong where he was to meet and marry Bridget Cooney. Presumably Thomas did not disclose that he was already married or perhaps said that his wife had died. It is hard to believe that Bridget was not at least aware of his convict past. However it appears that no memory of these events was preserved among his family and descendants.Little more is known of his parents or grandparents. However it seems that Thomas' father was still living in Warehorne at the time of the 1851 census. He died from cancer of the face on 23rd December 1858 in the Willesborough workhouse in East Ashford. He was recorded as being 73 yrs of age. Despite its grim reputation the workhouse was the place where many elderly or infirm spent their last days, not because they were paupers or long-term inmates, but because the workhouse infirmary was often the only place available once they could no longer be cared for at home. It is estimated that in the 19th century over six per cent of the population may have been in a workhouse at any time.

Hannah survived her husband and died at the home of her son James and daughter-in-law Susan, at 25 St Stephens Square, Southwark, Surrey on July 18th, 1861. Susan was present at the death and was the informant named on the death certificate which she marked with an 'X'. Hannah's age was given as 76 which would place her birth at around 1785, however ages provided by informants on death certificates are often inaccurate. The cause of death was given as 'paralysis'. 3

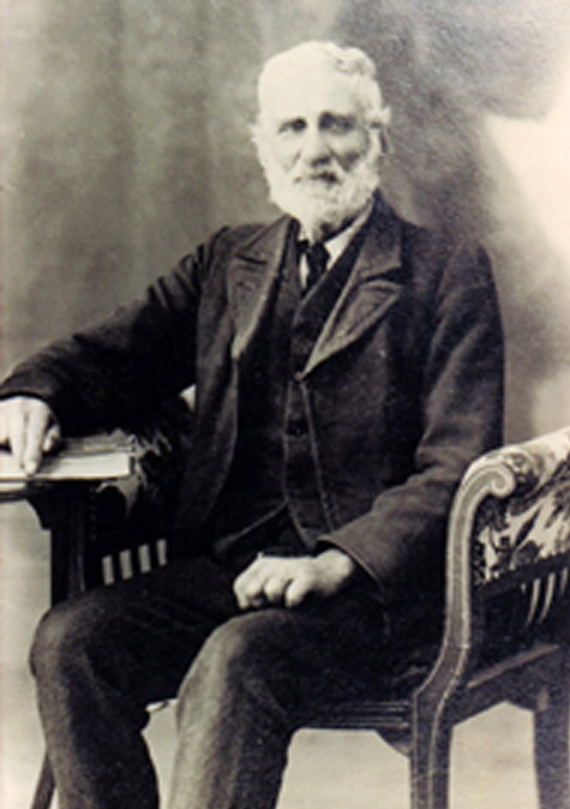

Thomas Benstead (photograph courtesy of Chris Upton)

Life in Australia must have been a financial struggle for Thomas and Bridget and their money problems seem to have accumulated. So much so that in April 1880 Thomas filed his insolvency schedule stating that he was unable to pay his debts which then totalled over 53 pounds. Money was owed to various creditors, mainly local traders, but it seems he had also borrowed various sums from individuals including his brother-in-law Thomas Cooney. He owned no property except for items of household furniture and a goat and some fowls which altogether were valued at only 4 pounds, leaving a deficiency of nearly 50 pounds. Thomas cited sickness of himself and family members, (his daughter Sarah had died in February of that year after an illness that had required hospitalization at various stages, and he himself had been unable to work at times due to severe rheumatism), unemployment and in particular, a loss of 30 pounds on a contract to supply railway sleepers for the railway in 1879, as reasons for his financial predicament. 4

The couple appear to have lived in the Point Henry district for most of their lives. They had at least eleven children including Hannah (whose name is recorded as Hannah Binstead on her birth certificate) and who probably died in infancy, John, Honorah (see next chapter), Sarah, Johannah or Hannah (whose name is also recorded as Hannah Binstead on her birth certificate, and who later married John Olson), Thomas, Bridget (who initially married Alfred Hooper, and following his death married James Allison), Patrick, James and Catherine (who married Robert Jarvis). Another child Mary Ann, died tragically of burns a couple of months before her third birthday 5 It was at Curlewis (near Pt Henry) that Bridget died on June 24th 1886. She was buried the following day and it is said that the toll of the church bell could be heard throughout the funeral procession to the cemetery at East Geelong where the burial took place. 6 Thomas survived his wife for many years until he died at Footscray in January 1917 at the age of 93 years. He is buried in the Footscray cemetery with his daughter Hannah and her husband John Olson. 7

Honorah, the second child of Thomas and Bridget Bensted was born at Pt Henry on July 28th 1859. No details are known of her early life until her marriage to a John Berry which took place in Colac on April 19th 1879. The marriage celebrant was Fr M Nelan and the ceremony was witnessed by Thomas Hugh Baum and Mary Annie Rourke. The address of both John and Honorah was given as Birregurra although it was noted that the usual address for Honorah was Curlewis. The couple's first child was born at Moolap on August 27th 1879, and given the name Bridget Theresa. The events that bring John Berry into this story will be recounted in the next chapter. 8

GO TO CHAPTER SEVEN FOOTNOTES

GO TO CHAPTER EIGHT

RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE